Introduction

Although the teaching-only academic role has been around for the better part of this century, it is still far from general acceptance within universities. In particular, although most research intensive universities now have in place career routes for teaching-only academics there is still a definite hesitancy from key sectors of academia when it comes to promoting teaching-only academics. From my ongoing research on teaching-only academics within research intensive universities, some typical questions that heads of departments and other senior managers are grappling with include:

- Is a professor promoted via the teaching route REALLY equivalent to a professor promoted on the basis of research?

- Isn’t promotion via the teaching route an easier route than promotion via research?

- What image do we present to other academics, to current and potential students, and to the wider outside world if we start promoting people on the basis of teaching?

These questions suggest a continued pre-occupation with research as a vehicle to achieving personal and institutional recognition and reward. Such views were reinforced and entrenched by the introduction of the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) in 1986, and its subsequent replacement by the Research Excellence Framework (REF) after 2008 (HEFCE 2012). However, with the recent passage of the Higher Education and Research Act 2017, the higher education landscape is poised for change.

The Act paves the way for the set up of the Office for Students (OfS) next year. This body will have responsibility for regulating standards and quality of education as well as oversee the introduction of private sector competition in the higher education sector. The Act also specifies the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) which is now already being used to assess the quality of teaching across universities (Department for Education 2016). It is expected that after 2020, the tuition fees that institutions can charge will be linked directly to the outcome of the TEF. This is likely to have far reaching consequences given that tuition fees have largely replaced teaching grants as the primary source of teaching income in universities. The Act therefore brings teaching and learning in higher education to the fore in a very forceful manner. In this article I argue that it is no longer business as usual in universities, and university recognition and reward systems need to change to take into account the changes taking place.

The changing academic role

Traditionally, the academic role has been viewed as comprising two main activities, namely teaching and research. But this is no longer the case. In recent times academic work has rapidly diversified (Locke et al. 2016). Coates and Goedegebuure (2012) sum up the diverse roles of academics as follows:

Academics train a country’s professional cadre, conduct scholarly and applied research, build international linkages, collaborate with business and industry, run large knowledge enterprises (universities), mentor individuals, train the research and the academic workforce, boost social equity, contribute to the creative life of the nation, develop communities, and contribute to broader economic development. And this list could easily be expanded.(Coates and Goedegebuure 2012)

This proliferation in academic functions is a direct result of the many pressures that have been brought to bear on universities. These pressures include(Locke 2014):

- the rapid expansion of higher education as more and more students opt to proceed from high school to university as opposed to going into work

- the reduction of public funding, coupled with the transfer of most of the costs associated with higher education from government to individual students

- increasing demands on universities from students, government and employers.

Despite the increasing diversity in academic activities and subsequent specialisation growing specialisation of academic role, policies and practices for promotion and recognition have failed to keep pace (Locke et al. 2016). For instance, across the higher education sector, there is still a widely-held perception that the criteria for reward and recognition in universities is heavily skewed towards those academics in traditional research and teaching roles(Locke et al. 2016). In particular, research remains the main activity of choice for those seeking job security and career progression (Locke 2014). Even those academics primarily employed on teaching-only contracts still strive to keep up with their discipline-specific research even though this is not part of their job remit. Such an approach has the effect of increasing academic workloads and affecting academic performance in the roles that they are employed in (Locke et al. 2016). It is therefore imperative that the recognition and reward structures in higher education need to change in line with changing academic work.

The Need for flexible promotion criteria for ALL academics

As the recent passage of the Higher Education Act 2017 clearly demonstrates, the modern day university now faces new challenges and expectations. To survive in this new environment, the modern university now needs to demonstrate excellence in a number of areas, and these areas are not necessarily compatible. First, to successfully attract research funding, and postgraduate students, the modern day university needs to present itself as a centre for research excellence. At the same time, the same institution has to position itself to students and to the outside world as a centre for excellence in education.

In addition, in compliance with the new Act, the institution has to be seen to be responsive to the needs of the community, for example, through having an effective widening participation programme, and supporting the local industry and economy. To achieve all this, the institution has to submit its institutional activities to external assessment and evaluation. In the UK this includes the Research Excellence Framework (REF) for evaluating research, the recently introduced Teaching Excellence Framework for evaluating teaching, the National Student Survey (NSS) for assessing the student experience, and the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) for assessing the employability of its graduates. It is also very telling that both the NSS and DLHE outcomes are being used as inputs to the TEF.

For an institution to excel in each of the above roles, it has to identify, retain and reward qualified individuals to carry out each of these the tasks. However, the potential for conflict and confusion arising out of attempting to satisfy all of the above performance evaluations cannot be underestimated. Brew et al. (2017) suggest that in the current university environment, academics are faced with ambiguous and contradictory messages regarding the nature of their jobs and what is expected of them. This includes contradictory official accounts of academic work as well as contradictory messages from external stakeholders such as government.

It is therefore necessary for universities to develop clear, unambiguous recognition and reward systems that cover all forms of academic specialisation, including teaching-only academic roles. Not doing so will lead to a situation whereby the university system is, in the first instance, unable to attract and retain the “best and brightest” to join the profession, and in the second instance, unable to identify and reward the most productive for their work, and weed out those who are unsuited for academic work.(Altbach and Musselin 2008)

Obstacles to recognising and rewarding teaching and learning

Cashmore et al. (2013) identify two major obstacles standing in the way of effective reward and recognition of teaching in higher education. The first one is institutional culture. This is best illustrated by the fact that although most universities now have in place clear routes for promotion on the basis of learning and teaching, their effective implementation still seems to be lacking (ibid.).

Another obstacle to rewarding excellence in teaching is that, unlike research, teaching does not have a clearly defined, coherent and widely-used set of criteria for evaluating excellence (Cashmore et al. 2013). Whilst the evaluation of research excellence is based primarily on publications and grant income, with teaching it is not as clearly cut. Compared to research, teaching encompasses a wide range of activities and roles, which means that a more diverse range of evidence is required to demonstrate excellence. In addition to this, such evidence is often qualitative in nature, thereby making it more difficult to assess excellence in teaching compared to research (Cashmore et al. 2013).

Emerging drivers for recognising and rewarding teaching and learning

Government concerns regarding the quality of university-level teaching is now an important contributory factor towards the recognition and reward of teaching-focussed academics. This started first as a “nudge” by government to higher education institutions. For instance, in 2003, government made the following observation in its white paper entitled “the future of higher education” (Department for Education and Skills (DfES) 2003:51):

In the past, rewards in higher education – particularly promotion – have been linked much more closely to research than to teaching. Indeed, teaching has been seen by some as an extra source of income to support the main business of research, rather than recognised as a valuable and high-status career in its own right. This is a situation that cannot continue. Institutions must properly reward their best teaching staff; and all those who teach must take their task seriously.

According to the government, the TEF has been introduced a way of “better informing students’ choices about what and where to study, raising esteem for teaching, recognising and rewarding excellent teaching and better meeting the needs of employers, business, industry and the professions” (Department for Education 2016). Following the classic carrot and stick scenario, institutions are now being encouraged, if they so wish, to use their teaching recognition and reward schemes for staff, together with their impact and effectiveness, as evidence for institutional teaching quality. This also includes progression and promotion opportunities for staff based on teaching commitment and performance (ibid.).

In the 2003 white paper, the government also mandated the introduction of a new national professional standard for teaching and a new national body to develop and promote good teaching (Department for Education and Skills (DfES) 2003:7). The standard in question is the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF), and the body in question is the Higher Education Academy which also oversees the UKPSF framework on behalf of the higher education sector.

Cashmore et al. (2013) suggest that the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF), particularly the Senior and Principal Fellow recognition criteria, can serve as a basis for developing a framework for assessing teaching excellence. They suggest that any promotion criteria arising out of this must go beyond the UKPSF criteria. This is because the UKPSF’s primary purpose is to set the minimum standards for the various (ibid.). Table 1 below illustrates how the UKPSF can be mapped to individual levels on a potential teaching-only academic career route.

Table 1: An illustration of the three UKPSF recognition level(adapted from The Higher Education Academy (2011):

| Recognition level | Typical individual role/career stage | Examples |

| Fellow | Individuals able to provide evidence of broadly based effectiveness in more substantive teaching and supporting learning role(s). | Have substantive teaching and supporting learning role(s).

Successful engagement in appropriate teaching practices

Successful incorporation of subject and pedagogic research and/ or scholarship as part of an integrated approach to academic practice

|

| Senior Fellow | Individuals able to provide evidence of a sustained record of effectiveness in relation

to teaching and learning, incorporating for example, the organisation, leadership and/or and learning provision. |

Having responsibility

for leading, managing or organising programmes, subjects and/or disciplinary areas

Successful incorporation of subject and pedagogic research and/ or scholarship as part of an integrated approach to academic practice

Successful co-ordination, support, supervision, management and/ or mentoring of others (whether individuals and/or teams) in relation to teaching and learning |

| Principal Fellow | Individuals, as highly experienced academics, able to provide evidence of a sustained and effective record of impact at a strategic level in relation to teaching and learning, as part of a wider commitment to academic practice. | Successful, strategic leadership to enhance student learning, with a particular, but not necessarily exclusive, focus on enhancing teaching quality in institutional, and/ or (inter)national settings

Establishing effective organisational policies and/or strategies for supporting and promoting others (e.g. through mentoring, coaching) in delivering high quality teaching and support for learning

Championing, within institutional and/or wider settings, an integrated approach to academic practice (incorporating, for example, teaching, learning, research, scholarship, administration etc.) |

Adopting a more radical method: Rethinking the academic culture

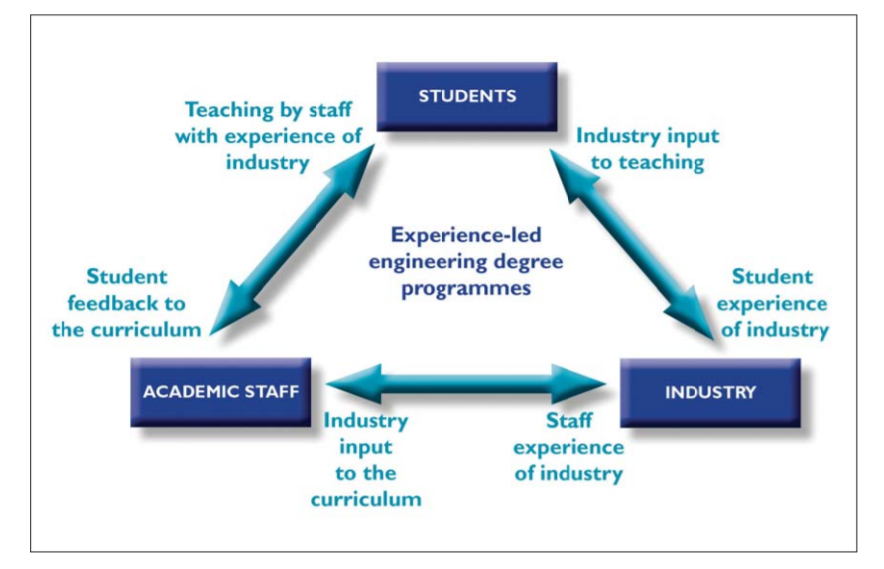

Research and teaching were not always treated as separate academic activities. Prior to the advent of the Research Excellence Framework and its predecessor the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), academics were expected to do both. Fung and Gordon (2016) argue that rather than just focussing on advocating recognition and reward for teaching-only academics, a more effective approach would be to develop a more equitable culture in terms of rewarding staff whereby education leaders are recognised as being at the same level as research leaders. They advocate the development of new models for research-based education which maximise the synergies between research and education for the benefit of the student. In such an environment, parity of esteem between education and research will develop naturally, and academic staff will play to their own individual strengths when seeking promotion.

Concluding remarks

The modern university is now expected to deliver on multiple fronts, including traditional research, learning and teaching, community engagement and enterprise (knowledge transfer and impact). In such an environment, individuals increasingly play to their strengths, and this is to the benefit of the institution, the economy and society. It is therefore pertinent that reward and recognition criteria should be developed to take account of the multiplicity of pathways that the individual academic chooses to take within the university.

References

“Higher Education and Research Act 2017”Chapter 29. City: HMSO: London.

Altbach, P. G., and Musselin, C. (2008). “The Worst Academic Careers — Worldwide” Inside Higher Education. City.

Brew, A., Boud, D., Crawford, K., and Lucas, L. (2017). “Navigating the demands of academic work to shape an academic job.” Studies in Higher Education, 1-11.

Cashmore, A., Cane, C., and Cane, R. (2013). “Rebalancing promotion in the HE sector: Is teaching excellence being rewarded.” Genetics Education Networking for Innovation and Excellence: the UK’s Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning in Genetics (GENIE CETL), University of Leicester, The Higher Education Academy.

Coates, H., and Goedegebuure, L. (2012). “Recasting the academic workforce: why the attractiveness of the academic profession needs to be increased and eight possible strategies for how to go about this from an Australian perspective.” Higher Education, 64(6), 875-889.

Department for Education. (2016). Teaching Excellence Framework: year two specification. London.

Department for Education and Skills (DfES). (2003). “The future of higher education”. City: HMSO: London.

Fung, D., and Gordon, C. (2016). Rewarding educators and education leaders in research-intensive universities. The Higher Education Academy.

HEFCE. (2012). “Research Assessment Exercise (RAE)”. City: HEFCE.

Locke, W. (2014). Shifting academic careers: implications for enhancing professionalism in teaching and supporting learning. The Higher Education Academy, York, England.

Locke, W., Whitchurch, C., Smith, H., and Mazenod, A. (2016). Shifting landscapes: Meeting the staff development needs of the changing academic workforce. The Higher Education Academy, York, England.

The Higher Education Academy. (2011). The UK Professional Standards Framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education. York, England.